I miss many things about working at a newspaper.

Sure, I continue to freelance (and to blog) to scratch my reporting itch, but it’s a different experience from working in a newsroom. I’m grateful I get to interview people and tell stories, but I sometimes miss the exhilaration of working side by side to dig into a big, important story or to race against deadline to pull the facts together.

What I *don’t* miss is knocking on the door of a grieving family to ask about a child who’s just died.

I’m not entirely sure why, but we have a desire to know more about the person who died and those left behind. Maybe it’s morbid curiosity, maybe it’s something bigger, like grieving as a community or trying to understand what happened so we can prevent future deaths. Maybe we want to picture ourselves in that family’s shoes, imagine how we might cope in similar circumstances, then say a prayer of thanks that it’s not us.

I’m an ENFP personality, which among other things means I’m sensitive and empathetic. When this worked to my advantage as a reporter, I was able to connect with people and get them talking, sometimes sharing more than they meant to. When it worked against me, I’d carry home people’s pain and suffering, to the point that I started seeing a therapist specifically to learn skills to put a little distance between other people’s feelings and my own.

As I watched coverage of the dreadful school shooting in Newtown, Conn., I pictured myself one of the journalists trying to tell that story — knowing that some families would want to tell the world about the person they’d just lost or maybe use the opportunity to call for gun reform, while others would slam the door feeling violated by a media vulture. Even the local newspaper has issued a plea for journalists to keep their distance:

The first time I had to interview a family that had lost a child I was still a teenager myself. I was working at my college paper and a fellow student died in a car wreck. I don’t remember if my editors asked me or told me to do the story, but I do remember sitting on the floor of my editor’s office, sobbing. I’d never met the student who died so they weren’t tears of my own grief, but from the weight of what these people I’d never met were feeling.

Around that same time, I was interning at the Saginaw News when two boys were killed by a hit and run driver. One had been spending the night at his friend’s house, and when the friend’s mother went to work that night, they’d gone on a night bike ride that turned fatal.

My editors sent me out to talk to the parents and I got a lesson in the possible extremes. One family welcomed me in, showed me their son’s bedroom as he left it, told me stories as we flipped through a photo album. The mother who’d been at work when the boys went out screamed at me, maybe suffering an acute case of “what if” guilt because she hadn’t been home to keep them safe, maybe just not wanting a stranger to intrude in her time of pain.

I thought of these experiences as I read a story on journalism site Poynter.org about journalists using social media to reach out to sources about the Newtown shooting.

In a story that begins, “Any journalist who’s had to ask grieving loved ones for an interview in the wake of a tragedy will tell you, it’s one of the hardest parts of her job,” Jeff Sonderman goes on to describe the challenge of being compassionate in 140 characters when asking for an interview.

Honestly, I felt the same about using the phone. I couldn’t assess the situation to see what I was interrupting, I couldn’t tell if the person on the other end was in the middle of a good, hard cry.

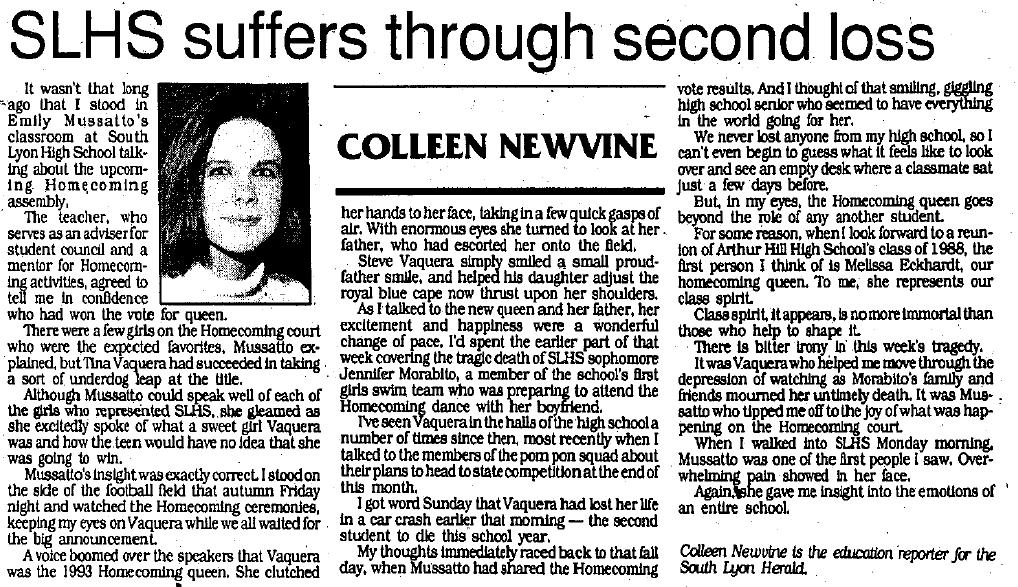

A few years out of college, I was the education reporter at a weekly newspaper. A pretty 16-year-old sophomore lost control of her car, it flipped and she was killed.

I steeled myself and went to talk to Jennifer Morabito’s family. I’m still blown away remembering how they treated me like a family friend. I sat with them as they cried about their loss and laughed at stories of how she and her brother teased each other and about how he gave her the nickname Baby Doll.

Then a few months later the high school’s homecoming queen died in a similar way, losing control of her car.

In a small town, the homecoming queen is something of a public figure, so I thought maybe Tina Vaquera’s parents would be receptive to talking about their daughter.

But I called, and was told no, rather firmly.

On my next job evaluation, my editor called out my lack of persistence in pursuing the Vaquera family.

Maybe another reporter would have tried harder, but the empathetic, sensitive one just wasn’t up to pressing the issue. I’m happy to leave that to journalists who are better at it than I was.

On reporting the pain of parents who have lost children

1 Comment

Mary Jean

I won’t miss it either, but I remember looking at it this way: For better or worse, tragedies are news, and if we’re going to be writing about the people who died the least we could do is give their loved ones an opportunity to say something. If they don’t want to, then back off. It can be done respectfully, though of course often it isn’t.

I’d totally forgotten about this until now: One time when I was working at the Flint Journal, some guy got killed. Racing around to put something together on deadline, someone pulled a clip from years earlier about something unsavory from the victim’s past. I can’t remember what it was, a drug conviction or something. It got played up pretty big in the story even though there was no evidence to support that the victim had been engaged in some illegal activity when he got killed. Let’s just say it wasn’t history’s best example of journalism. I was the evening cops reporter that day, and my assignment for the next day’s story was to talk to the victim’s family. This after the paper was already out with the headline that more or less said, “Joe Smith, One Time Drug Suspect, Murdered”. I dutifully called, reached his brother, and got an earful of expletives. Really, it didn’t even bother me because I was totally expecting it.

Leave a reply